China’s narrative of a continuous civilization spanning over 5000 years is a fundamental aspect of its national identity and pride. Frequently emphasized by leaders, scholars, and citizens, this assertion reflects not only cultural heritage but also serves as a pivotal element in contemporary political discussions. However, the historical accuracy of this claim warrants examination, raising questions about how we define history. Should we prioritize written records, or should we also consider cultural memory and oral traditions? This inquiry reveals the complexities of China’s historical narrative, intertwining folklore, archaeology, and an evolving comprehension of what civilization entails.

Chinese history was demonstrated by many evidences.

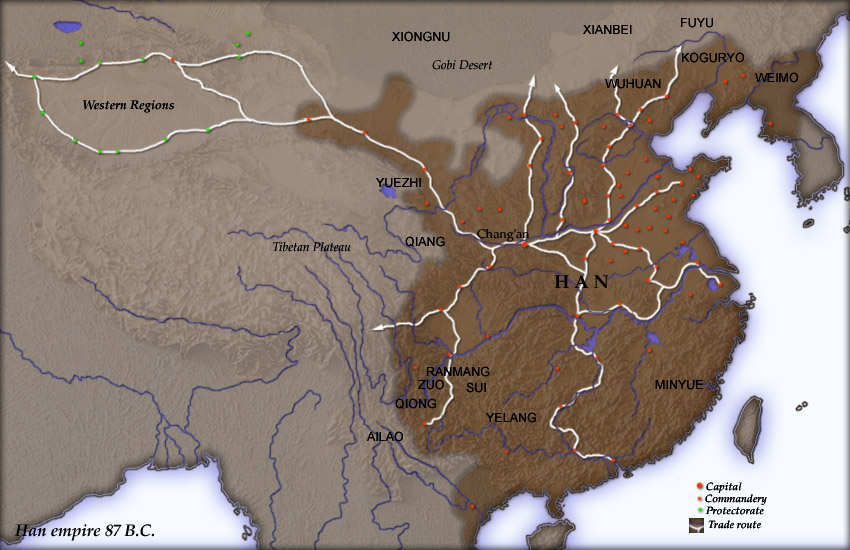

The assertion that China boasts 5000 years of continuous history does not merely stem from a singular historical standpoint but rather from various interpretations of historical documentation and cultural memory. The benchmarks set by Western historiography often begin with the earliest written records. In this context, the jiaguwen, or oracle bone inscriptions dating back to around 1200-1700 BCE, are crucial. These artifacts mark the dawn of documented Chinese civilization, suggesting a timeline that is approximately 3200-3700 years old, significantly shorter than the widely touted 5000 years.

However, the narrative of Chinese history is not solely reliant on written records. The concept of history as articulated by Chinese scholars includes legendary figures, such as the ‘three sovereigns and five emperors’ and the mythical Xia dynasty. These figures, deeply embedded in folklore, have become symbolic representations of Chinese cultural identity. Yet, the lack of tangible evidence for their existence raises questions about the validity of such claims. Can we consider a civilization birthed from myth and legend as continuous? This philosophical inquiry into the nature of history blurs the lines between fact and fiction, reflecting the complexities of Chinese identity.

The emergence of the Liangzhu site, an archaeological find that indicates human habitation dating back to 3000 BCE, further complicates the narrative. While the Chinese government seized this opportunity to reinforce the claim of a 5000-year civilization, it opens a Pandora’s box regarding the definition of what constitutes ‘Chinese civilization.’ The Liangzhu site demonstrates the presence of sophisticated cultures, but does it imply a unified civilization under a singular Chinese identity? The existence of diverse groups throughout China’s expansive territory challenges the notion of a monolithic culture.

The political implications of the 5000-year narrative are profound. The history of a nation is intrinsically linked to its identity, and for the People’s Republic of China, the promotion of this historical continuity fosters a sense of pride among its citizens. The government utilizes the notion of an ancient civilization to legitimize its authority and promote a narrative of resilience amidst global transformations. As the world evolves, the PRC’s emphasis on its historical legacy stands as a testament to its unique place in the global landscape.

However, the PRC’s relationship with its history is fraught with contradictions. While the government extols the virtues of Chinese civilization, it has also faced criticism for its historical preservation efforts. Scholars have pointed out the hypocrisy of glorifying a rich history while simultaneously allowing cultural artifacts and monuments to fall into disrepair or be destroyed. The Cultural Revolution marked a significant period of loss, decimating vast swathes of China’s cultural heritage. This juxtaposition raises a critical question: can a nation truly honor its past while neglecting its preservation?

The debate is related to political discourse and international relations.

The narrative of 5000 years of history is not merely an academic debate; it holds tangible consequences for political discourse and international relations. The PRC has often utilized this historical framework to justify its governance style and response to global norms, arguing that China’s ancient civilization necessitates a unique approach to governance. This perspective complicates the dialogue surrounding human rights and democratic reforms, as the government cites its historical context as a rationale for slower political progress.

While the debate surrounding the 5000-year claim is unlikely to yield a definitive answer, it offers invaluable insights into the interplay between history, identity, and politics in China. The origins of this claim reflect a rich tapestry of cultural heritage, showcasing how history can be both a source of pride and a tool for political ends. Exploring the nuances of Chinese history encourages a broader understanding of how civilizations define themselves, their legacies, and their place in the world. As we delve into this intricate history, we uncover not just the past of a civilization but also the dynamic relationship it continues to cultivate with its narrative in the modern world. Appreciation for Chinese history lies not solely in the numbers but in the richness of its stories, the complexity of its identities, and the lessons it imparts for future generations.

The debate surrounding whether the gap in Chinese history is a myth or a reality is complex. It requires an understanding that transcends mere dates and events, delving into how historical narratives shape national identity. This section aims to unpack the intricacies of this debate, examining the evidence, perspectives, and implications tied to the assertion of a 5,000-year continuous civilization.

Historians and scholars are consistently faced with the challenge of defining what constitutes a continuous civilization. The assertion that Chinese civilization spans 5,000 years is frequently anchored in a combination of written records and cultural memory. However, the lack of written records for a significant period often prompts skepticism about the continuity of this civilization. The period in question—roughly during the time before the Shang dynasty—leaves a vast expanse of time that, while undoubtedly rich in cultural development, lacks the concrete historical documentation that many Western scholars insist is essential to validate such claims.

The perspective that counters the notion of a monolithic, continuous history is backed by the understanding that various groups inhabited what is now modern China throughout its history. These groups often had distinct languages, customs, and social structures, contributing to a mosaic rather than a singular narrative. This heterogeneity complicates the idea of a unified Chinese civilization, as the question arises: can we truly consider such diverse societies as part of a singular civilization?

The challenge in ascribing permanence to Chinese civilization also lies in the significance of the mythical figures and dynasties that are often cited as foundational elements. The Xia dynasty, for instance, remains shrouded in legend, with historians like Sarah Allan arguing that the evidence for its existence is flimsy at best. Thus, the reliance on these mythical narratives raises critical questions about how history is constructed and who benefits from such constructions. The assertion that these legends contribute to a collective cultural memory implies that they serve a purpose beyond historical accuracy; they bolster a sense of identity and continuity amid changing realities.

Another element of this debate is the role of archaeology in shaping our understanding of Chinese history. Discoveries like the Liangzhu site, which suggests complex societies existed around 3000 BCE, have been hailed as evidence supporting the claim of an ancient civilization. However, critics argue that while these findings indicate advanced societies, they do not automatically translate to a unified Chinese civilization as defined by later historical narratives. This distinction is essential, as it points to the necessity of framing discussions around civilization in terms of cultural continuity versus political unity.

Moreover, the political implications of the 5,000-year narrative cannot be understated. In contemporary China, the Communist Party has utilized this historical framework to promote national pride, asserting that the country’s long-standing civilization provides legitimacy to its governance. This connection between history and politics reveals the critical role narratives play in shaping national identity and global perception. The PRC’s insistence on a continuous civilization serves as a foundation for its claims of sovereignty and cultural superiority, especially in a rapidly modernizing world where the past can provide a sense of stability and pride.

The international community’s perception of China’s long history, often reinforced by Western media and political discourse, complicates this narrative further. Foreign leaders and diplomats frequently reference China’s ancient civilization as a sign of its uniqueness. However, such references can inadvertently feed into a simplified understanding of a vastly complex history and facilitate a romanticized interpretation of what it means to be ‘Chinese.’ This phenomenon emphasizes how narratives can transcend factual antiquity and morph into powerful tools of political and cultural identity.

Discussions about the existence of a significant gap in the historical record often hinge upon defining what ‘history’ means in the context of civilization. While the Western tradition emphasizes verifiable, documented events, the Chinese perspective incorporates oral traditions, folklore, and cultural memory into its historical framework. This divergence in understanding history not only contributes to the debate about the 5,000-year claim but also reflects differing cultural approaches to understanding identity and legacy.

Furthermore, the very notion of a ‘gap’ in history might reflect more about historiographical biases than about the reality of cultural continuity. The lack of written records during specific periods does not equate to a lack of cultural richness or societal development. The absence of evidence does not diminish the lived experiences of people who contributed to those eras. Recognizing this complexity can lead to a more nuanced appreciation of history that embraces both its documented and undocumented facets.

As we navigate the intricate threads of this historical tapestry, it becomes clear that the debate is not simply about dates and records. It is about understanding how narratives shape perceptions and identities, both within China and beyond its borders. The question of whether or not there is a 1,500-year gap in history is less significant than the implications of how such narratives are constructed and employed. In a world where the past serves as a guide for the present and future, the interplay between history and identity will continue to be a vibrant area of discussion.

The ongoing debate regarding a potential 1,500-year gap in Chinese history—whether it is a myth or a reality—invites a critical reassessment of how we engage with historical narratives. Investigating Chinese civilization necessitates not only an examination of its documented past but also an appreciation for the rich stories, cultural memories, and diverse identities that have influenced its development over millennia. As we delve deeper into the complexities of Chinese history, we should celebrate its intricacies and recognize how these narratives shape our understanding of civilization and collective identity, encouraging us to look beyond mere dates to the vibrant stories that resonate through time.

Related posts:

China’s Five-Thousand Year History: Myth or Reality?

History of China

China and the Myth of 5,000 Years of History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/120424-jennifer-lopez-jeans-lead-3ababb7f27cc4dbb966563d220618e16.jpg)