In the annals of history, the Ancient Egyptians are known for their advanced civilization and their contributions to the world in various fields such as architecture, mathematics, and medicine. However, one peculiar belief that has intrigued scholars for years is the notion that Ancient Egyptian boys could menstruate, a rite of passage into manhood. This belief, as we now understand, was a misinterpretation of a medical condition caused by a parasitic disease known as schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis caused by Schistosoma worms

Schistosomiasis, also referred to as snail fever, bilharzia, or Katayama fever, is caused by blood flukes, parasitic flatworms of the genus Schistosoma. The disease manifests in two major forms: intestinal and urogenital, each caused by different species of blood fluke. The species and their geographical distribution are as follows: Schistosoma mansoni, found in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, Brazil, Venezuela, and Suriname; Schistosoma japonicum in China, Indonesia, and the Philippines; Schistosoma mekongi in certain districts of Cambodia and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Schistosoma guineensis and related S. intercalatum in the rainforest areas of central Africa; and Schistosoma haematobium in Africa, the Middle East, and Corsica (France).

The disease primarily affects poor and rural communities, especially those without access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation. It is estimated that at least 90% of those requiring treatment for schistosomiasis live in Africa, where the disease is most prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. Schistosomiasis is not only a health issue but also an economic one, as it can disable more than it kills. In children, it can cause anemia, stunting, and a reduced ability to learn, while in adults, it can affect the ability to work and, in severe cases, result in death.

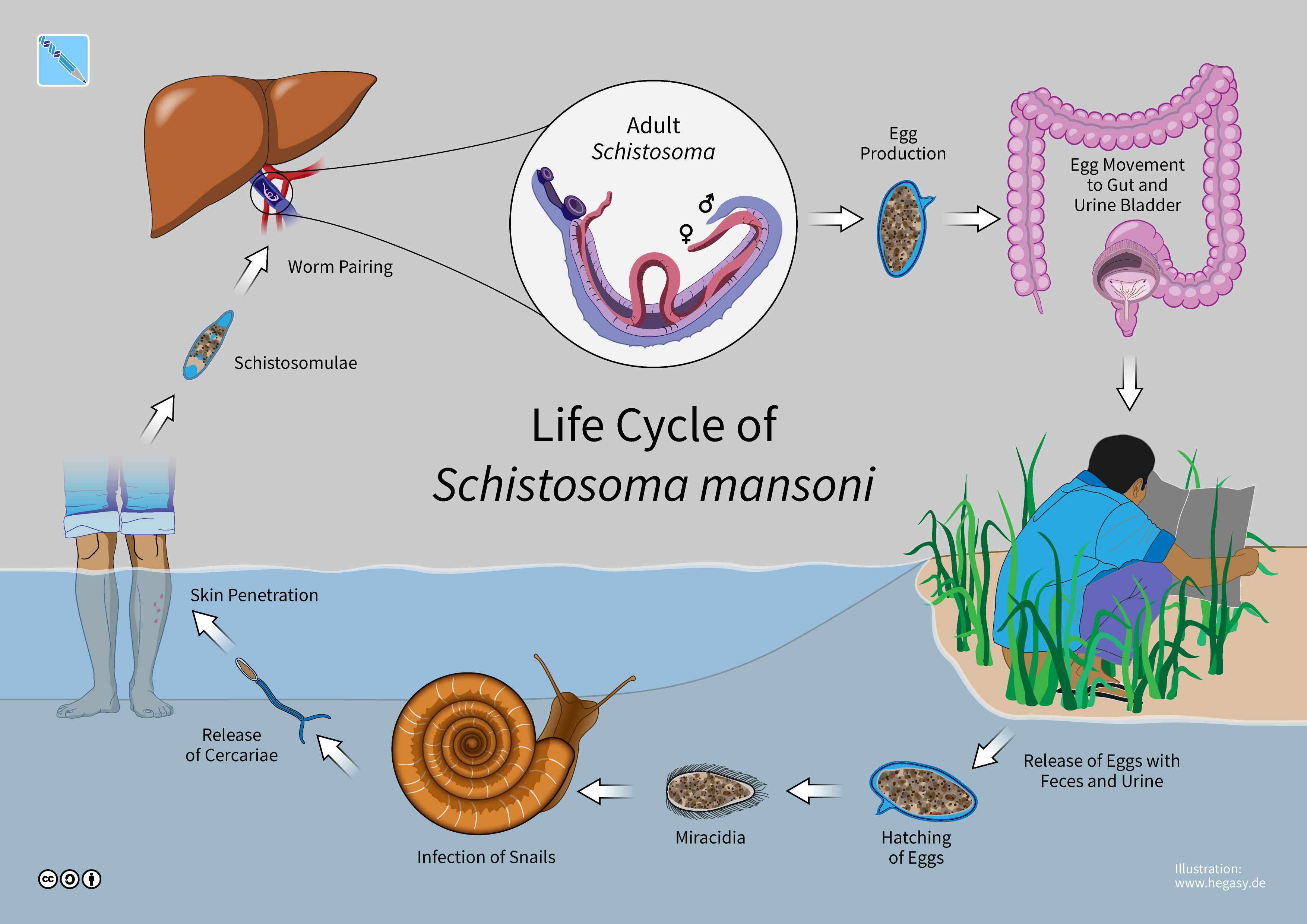

The transmission of schistosomiasis occurs when people come into contact with water infested with the larval forms of the parasite, released by freshwater snails. The larvae penetrate the skin and develop into adult schistosomes within the body. Adult worms live in the blood vessels, where females release eggs. Some eggs are expelled in the feces or urine, continuing the lifecycle, while others become trapped in body tissues, leading to immune reactions and progressive organ damage.

Symptoms of schistosomiasis

They are mainly due to the body’s reaction to the eggs. Intestinal schistosomiasis can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, and blood in the stool. Urogenital schistosomiasis often presents with haematuria (blood in urine), and can lead to kidney damage, bladder fibrosis, and in advanced cases, bladder cancer. In women, it may cause genital lesions and vaginal bleeding, while in men, it can affect the seminal vesicles and prostate.

Diagnosis of schistosomiasis is typically through the detection of parasite eggs in stool or urine specimens. For urogenital schistosomiasis, a filtration technique is used, while the Kato-Katz technique is employed for intestinal schistosomiasis. In non-endemic or low-transmission areas, serological and immunological tests may indicate exposure to infection.

The economic and health effects of schistosomiasis are considerable. The disease disables more than it kills, causing chronic conditions that can result in death. The number of deaths due to schistosomiasis is estimated at 11,792 globally per year, but this figure is likely underestimated. The disease’s impact on children’s growth and learning, as well as on adults’ work capacity, underscores the need for effective prevention and control measures.

Prevention and control of schistosomiasis involve large-scale treatment of at-risk population groups, access to safe water, improved sanitation, hygiene education, and snail control. The World Health Assembly’s new neglected tropical diseases road map for 2021–2030 aims to eliminate schistosomiasis as a public health problem and interrupt its transmission in selected countries. The WHO strategy focuses on reducing disease through periodic, targeted treatment with praziquantel, a safe and low-cost medication effective against all forms of schistosomiasis.

Despite the challenges, there have been successful schistosomiasis control efforts in countries like Brazil, Cambodia, China, Egypt, and others. Over the past decade, scale-up of treatment campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa has led to a significant decrease in the prevalence of the disease among school-age children. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a setback, with a 38% drop in treatment coverage compared to 2019. Continued efforts are necessary to combat this disease and improve the lives of those affected by it.

As we delve into the global impact of schistosomiasis and the concerted efforts to combat it, we must acknowledge the staggering statistics that frame this public health challenge. With an estimated 251.4 million people requiring preventive treatment in 2021, the scale of this disease is immense. Schistosomiasis transmission has been reported from 78 countries, but targeted large-scale treatment is necessary in 51 endemic countries with moderate-to-high transmission.

Preventive measures for combating schistosomiasis

The battle against schistosomiasis is multifaceted, involving a combination of medical intervention, access to clean water, improved sanitation, and public education. The cornerstone of medical intervention is the administration of praziquantel, a medication that is both effective and low-cost. This treatment is particularly crucial for at-risk populations, including pre-school-aged children, school-aged children, adults in endemic areas, and individuals with occupations that involve contact with infested water.

The World Health Organization (WHO) plays a pivotal role in coordinating the global response to schistosomiasis. Through the development of technical guidelines and tools, WHO supports national control programs in their efforts to reduce the prevalence of this disease. The organization’s strategy emphasizes the importance of periodic, targeted treatment to reduce disease morbidity and prevent the development of severe, chronic conditions.

Despite the availability of effective treatment, the reach of preventive chemotherapy remains limited. In 2021, only 29.9% of people requiring treatment were reached globally. This figure is even more concerning when considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a 38% drop in treatment coverage compared to 2019. The pandemic has undeniably hindered progress, but it has also highlighted the resilience of public health initiatives and the need for sustained efforts.

The economic and health effects of schistosomiasis are profound. The disease can lead to chronic conditions that significantly reduce an individual’s quality of life and ability to work. In children, the impact on growth and learning can be particularly detrimental, although these effects are often reversible with treatment. The estimated global death toll from schistosomiasis stands at 11,792 per year, a figure that likely underestimates the true burden due to hidden pathologies such as liver and kidney failure, bladder cancer, and complications from female genital schistosomiasis.

Environmental factors play a significant role in the transmission of schistosomiasis. Development schemes and modifications to the environment can facilitate the spread of the disease, as can migration and population movements. The rise of eco-tourism and travel to remote areas has also led to an increase in cases among tourists, who may experience severe acute infections.

Prevention and control measures are critical in the fight against schistosomiasis. Access to safe water, improved sanitation, and hygiene education are essential components of a comprehensive strategy. Snail control and environmental management also contribute to reducing transmission. The WHO’s new neglected tropical diseases road map for 2021–2030 sets ambitious goals for the elimination of schistosomiasis as a public health problem and the interruption of its transmission in selected countries.

The frequency of treatment is determined by the prevalence of infection in school-age children. In high-transmission areas, annual treatment may be necessary for several years. Monitoring the impact of control interventions is essential to adapt strategies and ensure their effectiveness.

Successful schistosomiasis control efforts have been implemented in countries such as Brazil, Cambodia, China, Egypt, and others. Over the past decade, treatment campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa have led to a significant decrease in the prevalence of the disease among school-age children. However, the journey towards the elimination of schistosomiasis is far from over. Continued investment in treatment, research, and infrastructure is vital to sustain progress and ultimately achieve the WHO’s goals.

The fight against schistosomiasis is a testament to the power of global health initiatives and the importance of persistent, coordinated action. As we forge ahead, let us be guided by the lessons of the past and the hope for a future free from the burden of this ancient disease. With unwavering commitment and collaboration, we can turn the tide against schistosomiasis and improve the lives of millions around the world.

Related posts:

Schistosomiasis

Nature Reviews Disease Primers

Schistosomiasis