In 1969, a teenager by the name of Robert Lee Rayford passed away under mysterious circumstances which would plague the medical community for decades. Born on February 3, 1953, in St. Louis, Missouri, this young African American’s life took an unfathomable turn when he began experiencing severe health issues at the tender age of 15. His story is not just a tale of medical enigma but a poignant reminder of the complexities surrounding the early days of AIDS in America.

Rayford’s health began to deteriorate in early 1968, leading to his self-admission to City Hospital in St. Louis. Covered in warts and sores on his legs and genitals, suffering from severe swelling of the testicles and pelvic region, Rayford’s condition was both perplexing and alarming. What made his case even more baffling was the severe chlamydia infection that had unusually spread throughout his body. Despite the doctors’ efforts to understand his condition, Rayford declined certain examinations and remained largely uncommunicative, a fact that added layers of complexity to his diagnosis.

The medical team, including Dr. Memory Elvin-Lewis, faced a perplexing challenge. Rayford’s symptoms defied the medical knowledge of the time. His shortness of breath, the spread of his infection, and his overall decline were reminiscent of conditions not yet known to medicine. By March 1969, his symptoms had worsened, culminating in his death due to pneumonia on May 15, 1969. However, it was the post-mortem discovery of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare cancer and an AIDS-defining illness, which set the stage for a medical investigation that would span decades.

The mystery of Rayford’s illness was initially documented in a 1973 medical journal, but it wasn’t until the identification of HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s that his case was revisited with a new perspective. The discovery of HIV in 1983 and its rapid spread within certain communities brought about a scientific race to understand its origins. Rayford’s case, with his symptoms and the post-mortem findings, became a crucial piece of this puzzle.

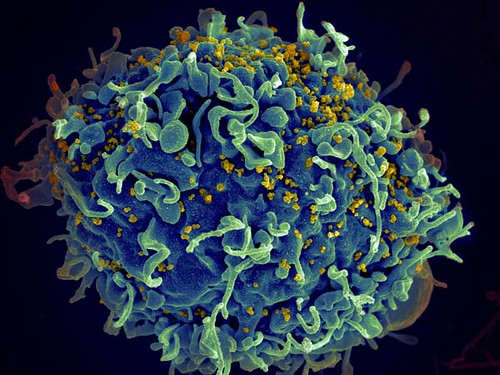

In the late 1980s, preserved tissue samples from Rayford’s autopsy were tested, revealing antibodies against HIV. This was a groundbreaking discovery, as it suggested that Rayford might have been infected with a virus closely related or identical to HIV-1, the primary cause of AIDS. The implications were profound, indicating that AIDS might have been present in North America well before it was officially recognized in 1981. However, despite these findings, Rayford’s mode of acquisition of the virus remained a topic of speculation among researchers.

Rayford’s life and untimely death shed light on the socio-economic conditions of African-American families living in St. Louis during the 1960s. Raised by a single mother in a working-class neighborhood, the hardships and struggles faced by the Rayford family are reflective of the broader challenges within the community. This context is crucial in understanding the layers of complexity surrounding Robert Rayford’s case and the initial barriers to diagnosing his condition.

The story of Robert Rayford is a testament to the gaps in our understanding of diseases and how they spread. It challenges preconceived notions about the origins of AIDS in America and underscores the importance of scientific inquiry and perseverance. As researchers continue to piece together the history of HIV/AIDS, Rayford’s case remains a poignant reminder of the human faces behind the numbers and the crucial need for empathy and understanding in the face of medical mysteries.

Deciphering the historical puzzle surrounding Robert Rayford’s illness requires diving deep into the complex interplay between medical science, societal factors, and the circumstances of Rayford’s life. The quest to understand his condition has been a journey fraught with challenges, disappointments, and groundbreaking discoveries, painting a vivid picture of the early days of AIDS research and the lengths to which scientists have gone to unravel its mysteries.

When Robert Rayford died in 1969, the concept of AIDS, let alone HIV, was nonexistent in the medical community. It wasn’t until the discovery of HIV in 1983 and its subsequent identification as the cause of AIDS that researchers began to piece together the puzzle of Rayford’s condition. The initial failure to identify HIV in Rayford’s tissue samples in 1984, followed by the success of the 1987 tests using the Western blot method, underscores the rapid evolution of scientific understanding and technology.

Moreover, the speculation that Rayford may have been a victim of sexual abuse or exploitation underscores the complexities of his case and the need for a nuanced understanding of the factors contributing to his infection. The absence of travel outside the Midwestern United States and lack of blood transfusion history point to sexual contact as the likely mode of transmission, raising important questions about the pathways through which HIV could have spread during that time.

The quest to understand Robert Rayford’s illness and its implications for the history of HIV/AIDS is a testament to the dedication of researchers and the importance of preserving medical samples. While the full truth of Rayford’s case may never be known, it serves as a powerful reminder of the human cost of disease and the critical need for ongoing research and education in the fight against AIDS.

Essentially, Robert Rayford’s story is not merely a medical anomaly; rather, it is a touching narrative that is interwoven with the broader history of AIDS, mirroring the difficulties of early diagnosis and the potential for neglected cases in the annals of medical history. As research continues, Rayford’s legacy endures, serving as both a cautionary tale and a beacon of hope for future breakthroughs in our understanding of HIV/AIDS.

Related posts:

Robert Rayford

A mystery illness killed a boy in 1969. Years later, doctors believed they’d learned what it was: AIDS.

BOY’S 1969 DEATH SUGGESTS AIDS INVADED U.S. SEVERAL TIMES