The four capitalized letters of the word SPAM might seem simple at first glance, but they hold a history shrouded in mystery and intrigue. Ask anyone what SPAM stands for, and you’re likely to get a variety of answers, ranging from humorous guesses to serious attempts. For decades, people have speculated about the true meaning behind this famous canned meat’s name. While it may be common pantry fare today, its name and significance have sparked curiosity worldwide.

Hormel Foods, the creator of SPAM, reveals that the true name meaning is a closely guarded secret known by only a select few, enhancing its allure for both enthusiasts and critics alike. The official site suggests one popular theory that SPAM could stand for ‘spiced ham,’ but is that the whole story or just a compelling myth? The tale traces back to a New Year’s Eve celebration in 1936 when Hormel hosted a product-naming contest, and legend credits actor Kenneth Digneau with coining the term by merging ‘spice’ and ‘ham’—a clever twist that earned him a prize of $100.

However, the mystery doesn’t end there. Other theories have surfaced over the years. Some believe SPAM stands for ‘Shoulder of Pork and Ham,’ which aligns with its primary ingredients: high-quality pork shoulder and ham. Meanwhile, more imaginative—or critical—acronyms include ‘Scientifically Processed Animal Matter’ and ‘Stuff Posing As Meat.’ Another plausible interpretation is ‘Specially Processed American Meat,’ though Hormel has neither confirmed nor denied these claims. Even Hormel’s slogan, ‘Sizzle Pork and Mmm,’ seems to play into the ambiguity, offering a modern, tongue-in-cheek twist rather than an official explanation.

The essence of SPAM, however, lies beyond its name. Its simplicity—using just six key ingredients: pork shoulder, ham, salt, water, sugar, and sodium nitrite—has contributed to its enduring popularity. Originally developed in 1937 as an affordable and convenient meat option for American households, SPAM quickly rose to fame as a staple during World War II. Its long shelf life and easy preparation made it an invaluable resource for soldiers overseas. By 1941, over 100 million pounds of SPAM had been consumed by troops, leading to its introduction in countries throughout Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Despite its practicality, SPAM’s reputation has always been a mix of admiration and ridicule. Take, for example, the infamous ‘Scurrilous File’ compiled by Hormel during WWII, documenting complaints from soldiers tired of eating SPAM day in and day out. Even Jay Hormel, the man behind SPAM, had a complicated relationship with his creation. In a 1945 interview with The New Yorker, he admitted to feeling both pride and burden over its widespread association with his name, famously quipping, ‘Damn it, we eat it in our own home.

The product’s emergence as a culinary icon owes much to its adaptability and the cultural significance that developed in the post-war years. After the war, SPAM became a beloved ingredient in many global cuisines, transcending its humble beginnings. It’s fascinating to consider that while the true meaning of SPAM’s name remains elusive, its impact on the world is crystal clear. From ‘army-base stew’ in Korea to Hawaiian SPAM musubi, this canned meat has woven itself into the fabric of countless dishes and traditions worldwide.

And yet, the question persists: What does SPAM really stand for? Perhaps its enigmatic name is part of the allure, a clever marketing tactic that keeps people talking. Despite countless attempts to demystify it, SPAM’s name remains one of the great culinary riddles of our time. The real takeaway might be this: SPAM isn’t just a name; it’s a story, a history, and—most importantly—a taste that has stood the test of time.

Recipe details: Spam Musubi

Prep time: 25 min Inactive time:

Cook time: 30 min Total time: 55 min

Level: 55 min Servings: Makes 10 musubi

Total weight: 1569.5 g Calories: 2772.6 kcal

Energy: 2772.6 kcal Protein: 92.2 g

Carbs: 424.5 g Fat: 74.3 g

Dish Tags: Japanese, main course, lunch/dinner, Dairy-Free, Egg-Free, Peanut-Free, Tree-Nut-Free, Fish-Free, Sulfites

Ingredients:

5 cups cooked sushi rice, room temperature

5 sheets nori, cut in half lengthwise

1 (12 oz.) can Spam

6 tbsp soy sauce

4 tbsp mirin

4 tbsp sugar

Furikake, to taste

Cooking steps:

1. Cut Spam into 10 slices. Fry until slightly crispy. Remove and drain on plate lined with paper towels. In another pan, combine soy sauce, mirin and sugar. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat, then reduce to low. Add Spam slices, coating them in the mixture. When mixture has thickened, remove Spam from pan.

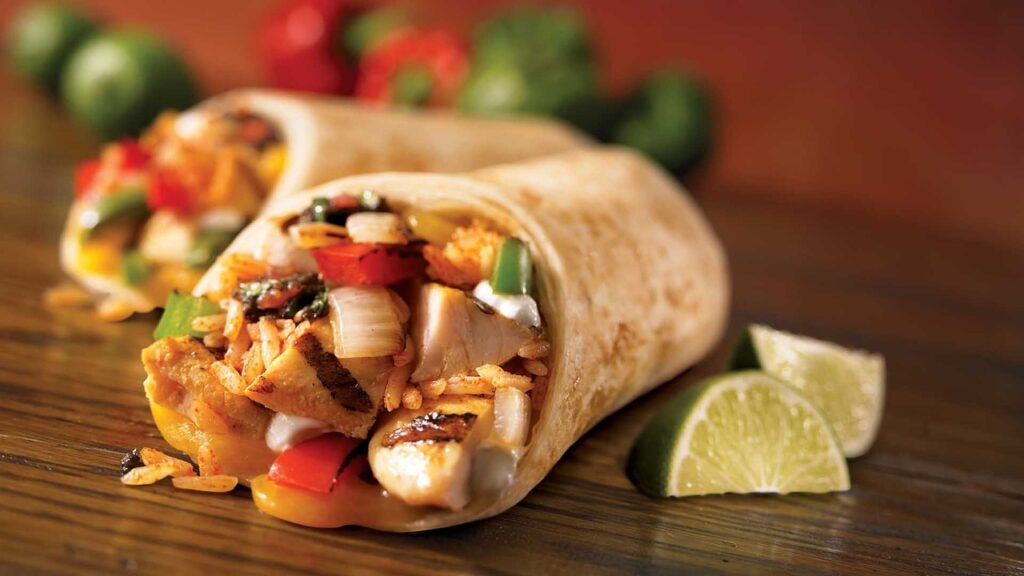

2. Lay a sheet of nori lengthwise on a clean surface. Moisten lower half of musubi maker (see Note), and place on lower third of nori. Fill musubi maker with rice and press flat until the rice is 3/4-inch high. Sprinkle rice with furikake. Top with slice of Spam. Remove musubi maker and keep in a bowl of warm water to keep it clean and moist.

3. Starting at the end towards you, fold nori over Spam and rice stack, and keep rolling until completely wrapped in the nori. Slightly dampen the end of the nori to seal it. Repeat with the other nine Spam slices, making sure to rinse off musubi maker after each use to prevent it from getting too sticky.

Get the recipe: Spam Musubi

From its humble beginnings, SPAM has carved out a unique place in cultural and culinary history. Its journey from an affordable protein source to an integral part of global cuisines showcases not only its versatility but also its surprising role as a cultural ambassador. After World War II, SPAM didn’t just stay in American pantries. It became a beloved ingredient in regions like Hawaii, Korea, and Southeast Asia, where it integrated deeply into local food traditions.

In Hawaii, SPAM has achieved legendary status. The creation of SPAM musubi, a sushi-inspired snack that combines a slice of SPAM with rice and nori, is just one example of how the canned meat has become a local favorite. Its portability and flavor make it an ideal grab-and-go meal, and you’ll find musubi in almost every convenience store on the islands. For Hawaiians, SPAM isn’t just a food; it’s a part of life. The annual SPAM Jam festival in Waikiki celebrates this love affair, drawing thousands of locals and tourists alike to enjoy SPAM-inspired dishes, from pizza toppings to flan.

Across the Pacific, SPAM’s popularity in Korea is a testament to its adaptability during times of hardship. During the Korean War, limited food supplies led locals to incorporate SPAM, obtained from American rations, into traditional dishes. Budae jjigae, or ‘army-base stew,’ is perhaps the most iconic example. This hearty dish combines SPAM with ingredients like kimchi, ramen noodles, and rice cakes, creating a fusion of flavors that represents resilience and innovation. Today, SPAM is seen as a premium gift item in Korea, often given during holidays in elegant packaging.

The Philippines is another country where SPAM has found a permanent home. Filipino cuisine embraces the canned meat in various forms, from SPAM fried rice to SPAM-topped sandwiches. Its versatility makes it an easy addition to traditional dishes, and it continues to be a pantry staple in Filipino households. In Guam, SPAM consumption is so high that it ranks among the top consumers per capita in the world. People there have developed countless recipes featuring SPAM, reflecting its integration into island life.

SPAM’s cultural influence extends beyond cuisine. The Monty Python sketch from 1970 added a layer of humor and pop culture significance to the brand. The repetitive chanting of the word ‘SPAM’ in the skit was so infectious that it eventually led to the term ‘spam’ being used to describe unwanted electronic messages. This quirky twist only further cemented SPAM’s place in both language and lore.

More recently, SPAM has seen a resurgence in the culinary world, particularly as chefs and food enthusiasts embrace its nostalgic and kitschy appeal. High-end restaurants have experimented with SPAM in gourmet dishes, elevating it from a simple canned meat to a culinary statement. Recipes like SPAM loco moco, a Hawaiian comfort food classic reimagined with gourmet flair, illustrate how SPAM straddles the line between highbrow and lowbrow dining. This newfound appreciation reflects a shift in attitudes, where SPAM’s history and cultural significance are celebrated rather than dismissed.

SPAM’s adaptability is also evident in its evolving product line. From classic SPAM to flavors like Jalapeño, Hickory Smoke, and Teriyaki, Hormel Foods continues to innovate, catering to diverse tastes and regional preferences. In Hawaii, the Teriyaki flavor has quickly become a favorite, while in Texas, the Jalapeño variety resonates with local palates. These innovations keep SPAM relevant in a rapidly changing food landscape.

At its core, SPAM remains a symbol of resilience and adaptability. Its long shelf life and ease of preparation have made it a pantry essential during economic downturns and natural disasters. During the 2008 recession, SPAM sales spiked as families sought budget-friendly meal options. Similarly, its role in disaster preparedness kits underscores its practicality and reliability.

Ultimately, SPAM’s remarkable global journey symbolizes its extraordinary capacity to bridge cultural and economic differences, transforming from a basic food preservation method into a culinary icon that sparks creativity and cultural pride. From the bustling streets of Seoul to the beautiful shores of Honolulu, SPAM continues to captivate and inspire, reminding us that often the simplest innovations leave the most significant and lasting impressions.

Related posts:

Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

What Does SPAM Stand For, Anyway?

A Brief History of Spam, an American Meat Icon